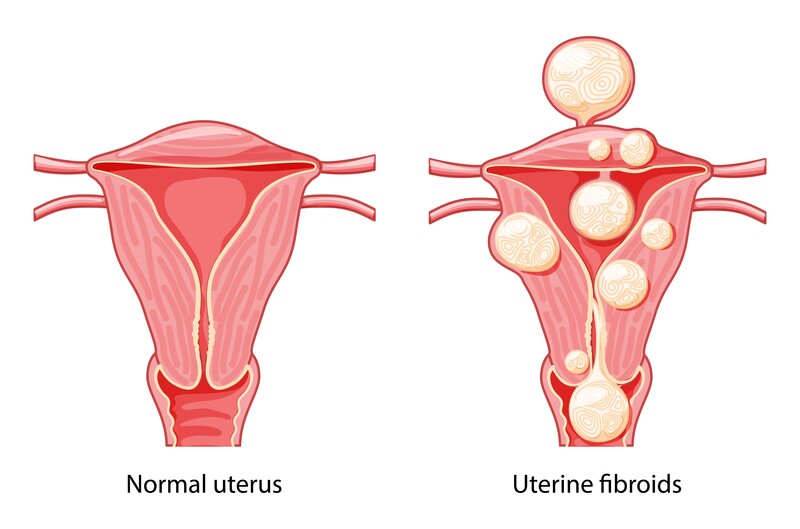

Understanding Fibroids: Non-cancerous muscle growths in the uterus

Fibroids, also known as uterine fibroids or myomas, are non-cancerous growths that develop within the walls of the uterus. We will discuss these growths, covering their definition, prevalence, risk factors, symptoms, and diagnostic approaches.

Fibroids growths arise from the muscle tissue of the uterus and consist of abnormal cells and fibrous tissue. They come in different sizes and can be solitary or multiple. Currently (2023), we believe that fibroids grow based on the hormones oestrogen and progesterone. The ovaries make these hormones and are usually influenced by the brain and medication.

Fibroids are quite common. Research suggests that a significant number of women, estimated between 20% and 80%, may develop fibroids. The prevalence can vary depending on age, ethnicity, family history and genetic predisposition. African-American and Japanese women tend to have a higher incidence of fibroids and may develop them earlier than women of other ethnic backgrounds. However, no signs exist that lifestyles, such as diet and sleep, influence fibroids’ appearance or growth. In our hospital, we do a lot of research on fibroids, trying to determine which factors influence their growth. Because fibroids grow based on ovarian hormones, they always shrink after menopause.

While most women may not experience noticeable symptoms, others may encounter mild to severe complaints. The most common complaints are blood loss or bulky complaints. Fibroids can cause heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding. Bulky symptoms, like pelvic pain or pressure, can be caused by the mass of the fibroid, which can be quite big. The bulk of the fibroid can also cause an increased frequency of urination. A more complicated problem is infertility. According to the FIGO classification, there are eight types of fibroids. But you can divide them into two clinically relevant groups: those inside or in touch with the uterine cavity and those growing more on the outside of the uterus. The first gives more complaints of bleeding problems, while the latter gives more bulky issues. Fibroids inside the uterine cavity can cause fertility issues, while those outside the uterus might not. More about fibroids and fertility in another blog post soon.

To uncover the presence of fibroids, the first step is a comprehensive medical history and a pelvic examination. Then an ultrasound scan is usually the first imaging technique. Preferably by vaginal ultrasound, even small fibroids can be visualised. MRI can be of added value when fibroids are very big or when it is needed to differentiate from something else.

Worries about cancer

Understandably, people may have concerns about fibroids and their potential to become cancerous. However, it’s important to note that fibroids themselves are non-cancerous growths. They are not inherently malignant, meaning they cannot transform into cancer. In extremely rare cases, a type of cancer called leiomyosarcoma can develop in the uterus’s smooth muscle tissue, where fibroids arise. However, it’s crucial to emphasise that leiomyosarcoma is extremely uncommon, accounting for less than 1% of uterine cancers. In the vast majority of cases, fibroids are benign and do not pose a risk of cancer.

In conclusion, fibroids are non-cancerous growths in the wall of the uterus. Although their exact cause remains uncertain, hormonal factors, genetics and age may contribute to their development. Understanding the definition, prevalence, risk factors, symptoms, and diagnostic approaches associated with fibroids is vital for early detection and appropriate management.

I personally see quite a lot of patients with fibriods. And it’s a very challenging problem, because many patiente either experience very little complaints. A fibroid can be found by coincidence or by a fertilty doctor. In my personal opinion one of the difficult things is the follow-up. We know from previous studies that fibroids grow about 1 cm per year. If a fibroid indeed grows that slowly, and someone has no complaints, it doesn’t make sense to check on it every year. But sometimes they grow faster. We might be able to determine with doppler ultrasound which fibroids grow faster, but not yet. And if a fibroid grows bigger, but still gives no complaints, should you treat? When should you treat something to prevent complications? And how many side-effects or risks should you accept? These are the complicated questions I discuss with my patients on the Amsterdam UMC Uterine repair center. I will discuss treatment in a different blog post.

Robert de Leeuw

If you have any personal experiences, thoughts, or additional insights about fibroids, we invite you to share them in the comments below. Your input may provide valuable perspectives and support for others navigating this common condition. Let’s foster an open and informative discussion about fibroids.

Leave a Reply